“Semiotics” is a fancy fucking word, isn’t it? In these dark days when idiocy is valorized and “smart” has somehow come to mean “elite,” i.e. “suspect and evil,” I cling to the fact that I know what words like “semiotics” mean: “the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation.” What is a sign? It can be literally a STOP sign, a signal for you to slow your car at an intersection. It is the very words typed into this website, which the act of reading transforms into pictures and ideas in a reader’s brain. Signs can be actual things. The graven idols on my home altar, including the Buddha, Shiva, Ganesha, and Medusa, are not objects of worship unto themselves. I don’t literally think they’re gods, just as most people of antiquity didn’t think they were (but were assumed to by Christian propaganda). They are signs for ineffable feelings and ideas like compassion, eternity, and protection. The Christian sign of the cross is an ultimate example of a semiotic sign: a simple “t” shape stands in for an entire mythology and worldview.

Incense is definitely a sign of more than literal smoldering plant matter. Back in the ancient days, our forebears burned animal flesh and blood to please the gods. We liked to eat cooked flesh, so it was natural to assume the gods would, too. The smoke rising upward was a sign not only of human prayers, but also of food for the gods. Eventually, our ancestors figured out that sacrifices of plant leaves, resins, and fragrant woods not only masked the gross smells of burning flesh, but were more beautiful-smelling offerings unto themselves. After all, resins of trees like copal, frankincense, and myrrh are all literally tree blood, and they certainly smell much better and last longer than animal blood. Eventually, incense became a sign for the ancient offerings of flesh. The Mayans formed copal into maize or tortilla shapes: a sign of them being godly food. One of the most famous verses of the Bible is Psalm 141:2: “Let my prayer be counted as incense before you, and the lifting up of my hands as the evening sacrifice!”

I argue that there is no better example of how signs can change and embody meaning than famous semiotician Umberto Eco’s novel, The Name of the Rose. While most of his writing is too impenetrably academic for most, in Rose, Eco managed to wrap the horse pill of semiotics into a tasty chocolate coating of Whodunit mystery. This easy-to-swallow treat can be enjoyed as a plain old murder mystery as well as a deep dive into the semiotics of Western thought. More than just the story of killings in an abbey, Rose describes the seeds of humanism, fanaticism, fundamentalism, capitalism, and other -isms that eventually grew into the structures of our current society. Not only that, but the novel transported me into a world long vanished: a Medieval abbey where the knowledge of ancients was laboriously copied by hand and transmitted via fragile pages of vellum. When I read it, I felt immersed in another bygone place and time…a time when people were deeply hungry for information, so much so that they hoarded it and painstakingly illuminated it because it was so hard to come by. It’s quite a contrast to now, when we’re drowning in it.

As I followed the adventures of Friar William and his novice, Adso, I was thrilled to discover a significant passage in Rose involving incense. Tasked with investigating a series of Revelations-themed murders, the detectives eventually find their way into the Aedificium, a magnificent library at the heart of a wealthy and mysterious Italian abbey. As they track the suspected killer, they become lost in the Aedificium’s maze of rooms, encountering funhouse mirrors and other obstacles meant to confuse and deter intruders.

Chief among these is a thurible burning incense. Brave Adso enters the room first.

I came to the threshold of the room from which the glow, quite faint, was coming. I slipped along the wall to a column that served as the right jamb, and I peered into the room. No one was there. A kind of lamp was set on the table, lighted, and it was smoking, flickering. It was not a lamp like ours: it seemed, rather, an uncovered thurible. It had no flame, but a light ash smoldered, burning something. I plucked up my courage and entered. On the table beside the thurible, a brightly colored book was lying open. I approached and saw four strips of different colors on the page: yellow, cinnabar, turquoise, and burnt sienna. A beast was set there, horrible to see, a great dragon with ten heads, dragging after him the stars of the sky and with his tail making them fall to earth. And suddenly I saw the dragon multiply, and the scales of his hide become a kind of forest of glittering shards that came off the page and took to circling around my head. I flung my head back and I saw the ceiling, of the room bend and press down toward me, then I heard something like the hiss of a thousand serpents, but not frightening, almost seductive, and a woman appeared, bathed in light, and put her face to mine, breathing on me. I thrust her away with outstretched hands, and my hands seemed to touch the books in the case opposite, or to grow out of all proportion. I no longer realized where I was, where the earth was, and where the sky. In the center of the room I saw Berengar staring at me with a hateful smile, oozing lust. I covered my face with my hands and my hands seemed the claws of a toad, slimy and webbed. I cried out, I believe; there was an acid taste in my mouth; I plunged into infinite darkness, which seemed to yawn wider and wider beneath me; and then I knew nothing further.

Lucky for Adso, William quickly drags him away from the noxious smoke. As Adso comes to, William deduces that the incense was made of a poisonous or psychoactive plant, “an Arab stuff, perhaps the same that the Old Man of the Mountain gave his assassins to breathe before sending them off on their missions,” i.e. hashish, a derivation of cannabis. This fascinating article suggests that the incense included henbane, a poisonous European herb containing tropane alkaloids that cause delirium, loss of consciousness, and even death. All plants containing these alkaloids are infamous in human culture. The most famous of these—coca—have fueled destructive dynasties of drug cartels in Central and South America for nearly a hundred years. Others—henbane, datura/ jimson weed, mandrake, or angel’s trumpet— feature widely in occult lore as flying aids for witches and brujos. They are also very beautiful. Every day, I see the dangling trumpets of brugmansia/ angel’s trumpet trees all over Hawai’i, growing innocently in neighbors’ gardens.

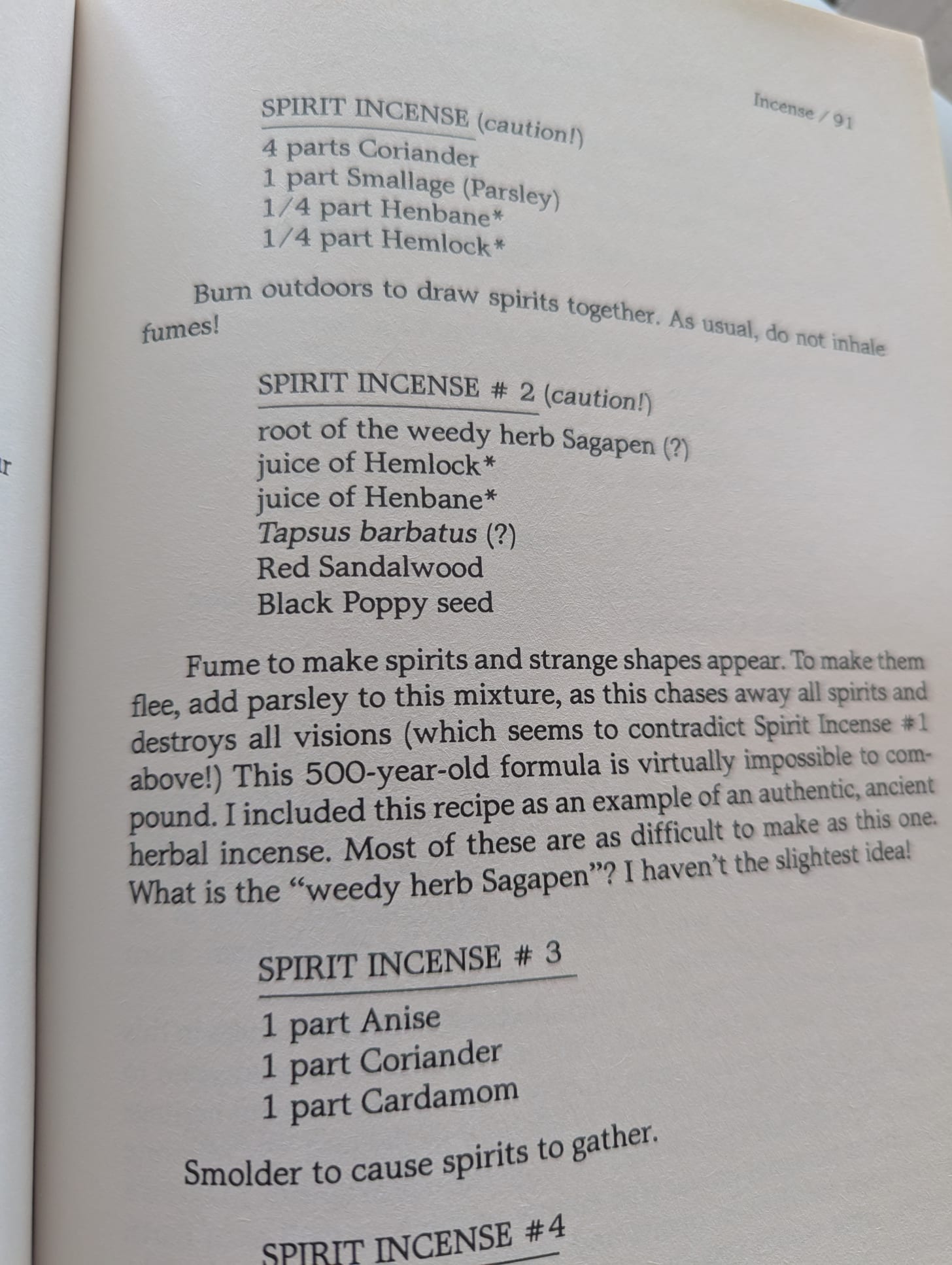

I lean towards henbane as the secret ingredient in The Name of the Rose’s deadly incense, as I’ve done enough cannabis in my time to know that it takes a lot of weed to make a body trip balls and pass out like poor Adso did. Just catching a whiff (even as a cannabis-virgin young monk) wouldn’t cut it. Curious, I consulted one of my incense recipe books of the more magic-with-a-k variety, The Complete Book of Incense, Oils, and Brews by Scott Cunningham. Sure enough, it listed a few very old incense recipes featuring henbane, with the asterisk warning of *do not try, poisonous.

The Name of the Rose made me want to create an incense that hinted at the power and mystery of the Aedificium without actually causing harm. I also wanted to evoke a Medieval abbey and the apothecary of herbs used by Rose’s herbalist, Severinus, who discusses at length the medicinal and poisonous varieties of plants he uses. One of these is valerian, a European herb so well known as an anxiolytic and sleep aid that Severinus mentions it only in passing: “valerian, whose properties you surely know.”

While so many items in my incense apothecary recall faraway places on tropical islands or vast deserts, valerian is one of the few that evokes the land of my ancestors. This very European herb, used as far back as ancient Rome and likely even earlier, has a deep, sour, medicinal funkiness that I love. It smells to me of comfort and nighttime. I struggled with insomnia for several years during my 30s. During those restless nights, I kept a bottle of valerian tincture next to my bed, its bitter taste improving to fair as it eased my anxious mind into sleep. One of my favorite Carl Neal incense recipes combines sandalwood, red wine, and valerian, and it’s been one of my go-tos for homemade incense ever since I tried it.

Frankincense and myrrh were natural choices to include as classic churchy scents. But what could act as a symbol of Adso’s vision-inducing incense? Henbane and other magic-with-a-k herbs tend to have a foul odor, and as much as I like to stretch my wings as an incense artist, I don’t want my incense to smell actively bad. I wanted just of hint of dank, and I found it with patchouli. Even the cheap, stale patchouli from Korea I bought from Amazon reeked mightily, so into the blend it went. Combined with tabu no ki as a binder and red sandalwood as a relatively scentless filler/ burn aid, the resins, valerian, and patchouli made for a sweet, yet powerful incense. I made a large batch into cones, leaves, and sticks. After a bit of curing, the result is one of the best combustibles I’ve made so far. The resins add a sweet elevation to the dark, earthy funk of valerian and the danky patchouli. I’m so happy with Aedificium, I’ve added the cones and joss sticks to my web store.

Alas, as industrialization encroached the the death of god was nigh, the deep meaning of incense fell by the wayside. While some pagan, Buddhist, and Christian folks still use it like the ancients did, for most, incense has come to signify either conspicuous consumption or a display of one’s personal taste. This ancient art, once valued by temple priests from Sinai to Rome to Egypt and China, is a shadow of what it used to mean: the presence of the holy.

Even so, there is a dearth of holy feeling in our world lately. Even in its diminished, commodified form, incense can still act as a doorway to an otherland outside of ordinary consciousness. Whether that means relaxation or revelation, natural incense invites us to stop, pause what we’re doing, and witness as a plant enters our bodies via the breath. The humble world of plants, which provide our greatest highs, our deadliest poisons, and all the foods and medicines in between these poles, speak to us in these moments, if we let them.

What do they say?

In another of Adso’s many visionary moments, he loses his virginity to a peasant girl. I think it’s telling that most of his metaphors involve the natural world. Not coincidentally, many of these metaphors involve specific ingredients used in incense.

Thy lips drop as the honeycomb, honey and milk are under thy tongue, the smell of thy breath is of apples, thy two breasts are clusters of grapes, thy palate a heady wine that goes straight to my love and mows over my lips and teeth. ... A fountain sealed, spikenard and saffron, calamus and cinnamon, myrrh and aloes, I have eaten my honeycomb with my honey, I have drunk my wine with my milk. Who was she, who was she who rose like the dawn, fair as the moon, clear as the sun, terrible as an army with banners?

This love, this intoxicating passion and need, is born of our beautiful home, of Earth.

Can anything be holier?

That second quote takes lines from the Song of Solomon, which I was reading just minutes ago for some reason. I agree with you that fragrance has been cheapened, and that losing a sense of holiness is indeed a loss. My personal opinion (as an ardent atheist / anti-theist and skeptic) is that we ought to cultivate a humanist sense of the sacred: a deep reverence for the arts, the body, and for *every second* of sentient life. That said, I don't know that it's possible to erase the meaning of fragrance; being that smell is the sense most strongly tied to memory, I feel that we constantly ascribe deep personal significance to the fragrances that live with us. For instance, before she died in an accident, I briefly stayed with my gran after I left school. She lived in a mildewy old council flat in the Scottish Borders. I have an expanding file that I've been using to store important documents from that time, and even all these years later, it still smells a little like that musty old flat. It about knocks me sideways emotionally every time I open that blue folder. In Michael Cousineau's "The Fragrant Path," Cousineau advises that we intentionally use incense as a part of our daily lives and family traditions, to build the association between fragrances and our lives.

This is really fascinating, thanks. Weirdly, I have never read Name of the Rose, despite my fascination with and academic interest in medieval Europe.